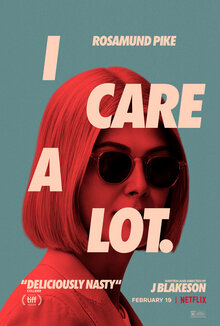

Years ago I began reading about guardianship abuse cases and how elderly had their rights stripped from them by unscrupulous guardians using the judicial system in Las Vegas.* The black comedy “I Care a Lot” staring Rosamund Pike and Peter Dinklage took an over-the-top spin on this topic, with one court scene that I found interesting and paralleled some of the facts in the Nevada cases. So the facts of Snell v. Ellis, 05-20-00642-CV, 2021 WL 1248276, at *7–8 (Tex. App.—Dallas Apr. 5, 2021, no pet. h.) intrigued me and deserve some discussion before we get to the always scintillating Texas Anti-Slapp discussion.

Plaintiff (Snell) is an attorney that ends up disoriented in a residential neighborhood (December 9) and is picked up by the police and hospitalized. Some unknown third-party filed an involuntary commitment proceeding in probate court resulting in Snell placed in a behavioral hospital (December 10). On December 12, Snell is notified of a probable cause hearing to detain him (December 13) until a trial (December 18). The notification also informs him that Defendant (Ellis) is his appointed attorney.

According to Snell: (1) he meets with Ellis and informs her he will represent himself; (2) she is not to be his attorney; and (3) Ellis then files a notice with the probate court that Snell cannot assist her with his hearing. It is unclear if a probable cause or trial occurred. What is clear is that Snell was detained in the behavioral hospital till December 27 (18 days from start to finish).***

Unsurprisingly, Snell sues Ellis for legal malpractice. Equally unsurprising, Ellis filed a Texas Anti-Slapp motion based on RTP (“Right to Petition for you newbies). Ellis alleged two hooks for protected communications: (1) a notification that Ellis filed with the probate court concerning her meetings with Snell; and (2) failure to notify the court of the communications with Snell that he did not want her to represent him.

With regard to the first hook of “notifications” it does not appear that Ellis argued much more than she was being sued for filing a notification with the probate court. As a result, the Dallas COA determined she had not established the specific communication in the court that is tied to her RTP. [Practitioners Note: it is always a good idea to advise the trial court of the specific links to the TCPA that are contained in the petition/counterclaim].

The Dallas COA easily dismissed the second hook based on “omissions.” The Dallas COA previously determined that failure to communicate does not trigger TCPA protections and noted its analysis of the TCPA is supported by the Ft. Worth COA, but in conflict with the Austin COA and San Antonio COA.

But the novel issues raised, kind of answered, and then left for everyone to ponder is whether an attorney being sued for legal malpractice can trigger the TCPA using communications he/she/they made on behalf of a client to the Court. In theory, this concept would apply to any case where the principal is suing the agent for communications the agent made for the principal. I will let the Dallas COA take it from here:

The more novel question, on the facts here, asks whether Ellis, as Snell’s attorney (and thus his agent), may rely on the notification she filed on Snell’s behalf for purposes of satisfying her burden under section 27.005(b)(1)(B). The plain text of section 27.005(b),17 long-standing rules regarding agency,18 and our decisions in other contexts19 suggest the answer is “no,” but because the parties have not raised it, we do not decide that question here. Instead, for purposes of this appeal, we assume, but do not decide, that the notification Ellis relies on constituted an exercise of Ellis’s right to petition under section 27.005(b)(1)(B). Even with this assumption, however, we agree with Snell that Ellis has not demonstrated that Snell’s legal action is based on or in response to Ellis’s notification.

Footnote 18 leaves little doubt as to how this particular panel views the TCPA’s application to this type of legal malpractice case.

Put another way, whatever communications Ellis made while purportedly representing Snell’s interests arguably are not her communications, but Snell’s, in the factual context here. They implicate Snell’s right to petition, not Ellis’s.

Turning back to the click bait title, if Rosamund Pike’s character in I Care a Lot was an attorney (she wasn’t) and she represented Peter Dinklage in a guardianship hearing (she didn’t) and he sued her for legal malpractice (that didn’t happen in the movie either) she might have trouble anti-slapping that claim in the Fifth Court of Appeals.

** https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Care_a_Lot (photo attribution as well)

***As a matter of course, I do not read the underlying petition in a TCPA appeal unless it is a dispute about whether you can have chickens in your neighborhood. In those rare situations, how can you not?